Lost in the Gloom: A Dream Mountain Goat Hunt Turns into a Nightmare

The difference between a dream hunt and heartbreak balances on a knife-edge ridge

THE FOG rolls up the mountain, hiding the old-growth forest below us and smothering any hopes we might have had of spotting a blacktail buck. We knew we wouldn’t see, let alone shoot, a deer today, but a little walk helps us escape the claustrophobia of our two-man tent.

Before handheld GPS became reliable and popular, wandering around in the mountains of Southeast Alaska on an intensely foggy afternoon was a good way to get lost—for good. But even with GPS marking our way through the gray, it’s obvious that the only thing to do is keep waiting for the haze to lift.

“Nietzsche wrote about mountain climbing and never left his room,” says Bjorn Dihle as we stare into the nothingness. “I always think about that when the mountain is socked in.”

I don’t know who Nietzsche is or what the hell Bjorn is talking about, so I just nod in agreement. I actually don’t know Bjorn that well at all. We met when I was on another assignment and he invited me to go deer hunting with him—and he also offered to put me in touch with one of his buddies who is a mountain goat hunting guide. I took him up on both.

But I’ve since learned a few things about my new hunting partner. He’s an understated wilderness badass. He’s skied across the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and guides months-long bear trips for the BBC. He and his two brothers are known around the town of Juneau as hardcore hunters, chasing everything from deer to goats to moose. Bjorn pushes through the thickest patches of Tongass National Forest bellowing, ‘Heyyyy, bear’ with almost the exact low, welcoming tone that one of my old rancher friends uses to warn his cows not to crowd their fence.

On the third day of our hunt, the fog clears, and I shoot a velvet buck on the back side of the mountain. The deer is small, the size of a young whitetail doe back home, and his hide is still warm and loose. We skin and quarter him quickly.

“We’ve never killed one this far back before,” Bjorn says as he slings on his backpack, which contains half the buck and will soon hold our entire camp. From here we side-hill for about a mile and then crest the ridge back to our tent. We pack up quickly and descend the mountain through the dark timber to the beach, where we’re picked up by a floatplane and whisked back to Juneau.

This hunt with Bjorn serves as a prelude to the mountain goat hunt that lies ahead. It’s an informative intro to the Tongass’ alpine, and I’ve learned the basics, mostly that I’m going to need more base layers or I’m going to be wet for the entire hunt. And also, goat hunting in Southeast Alaska is going to be just as tough as I’d imagined, maybe more so.

A Slog to the Alpine

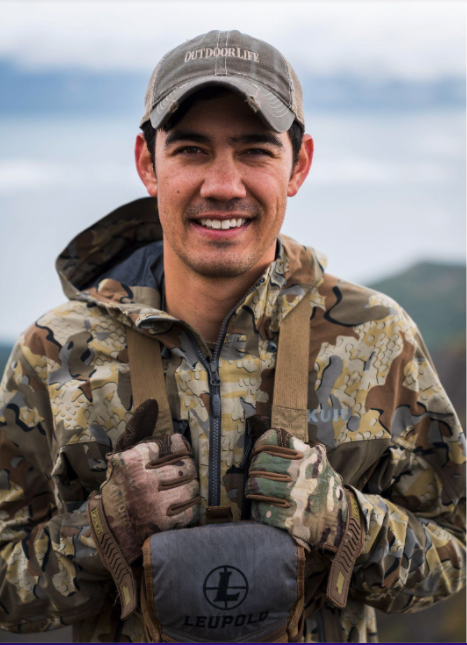

I meet my goat hunting guide, Lucas Mullen, that afternoon while Bjorn and I are unpacking from the deer hunt. He’s laid-back and short and looks wiry-strong as he paces back and forth on a slippery concrete barrier while we unload Bjorn’s car. Lucas is a mountaineer who got into goat hunting as a way to spend more time in the alpine. He guides brown bear hunters in the spring, and during the summer, he’s a commercial fisherman in the Lynn Canal, a 200-mile inlet running straight north from the ocean through the Chilkat Range. The mountains get steeper the deeper you go into the inlet, which creates a sort of wind tunnel effect that, when combined with the tides, can make for rough, dangerous seas.

“Even really serious fishermen, when they hear ‘Lynn Canal,’ they’re like, ‘I fucking hate that place,’” Lucas says.

This is where he and I will be hunting, or at least so we hope. Our plan is to boat up the canal, get dropped off on the beach, and then hike up into the Chilkat mountains. But it’s rained for 77 consecutive days by the time I arrive in Juneau (setting a new record), and the trend is continuing while I’m here. It’s not so much the rain that keeps us from traveling to our hunting spot but the wind that carries it. Every few minutes, Lucas checks the weather report, and every few hours, he calls his captain buddy to see if it’s calm enough for us to run the canal. For three days the report is the same: no-go. But this kind of delay is typical for many Alaska hunts, so I use the downtime to ice my knee and dry out my gear. By the time Lucas’ boat captain finally gives us the green light, I’m ready.

Joining the hunt is photographer John Whipple, who is built like a retired middle linebacker and has the unflappable temperament of a caretaker for the mentally ill—which he has been. After an uneventful boat ride, we throw on our packs, which are loaded with everything we’ll need to survive for five nights on the mountain, and begin our hike through the old-growth forest.

I’m fascinated but also intimidated by the mountains of the Tongass, which are not like the mountains I’ve hunted in the lower 48. The 10,000-foot peaks of Colorado might steal your breath, but there are usually roads, or at least trails, to get you into that high country.

Here the alpine is protected by a fortress of old-growth timber, devil’s club, deadfalls, and alder. You fight brush all the way, and you keep climbing until it’s so steep, rocky, and high that the alder brush can no longer find a place to cling to. Then you start hunting.

It doesn’t take much imagination to envision what an accident might look, and feel, like here. I can see myself slipping off a rain-slick log and snapping an ankle. Higher up I can visualize a careless step, then the sliding loose rocks, a desperate grab for handholds that don’t exist, and finally a bone-crunching crash. It’s this awareness that makes for very, very slow going. We pick our way over massive deadfalls and up steep slopes like boulderers working on new problems. There are no careless steps.

We make it to the alpine after a solid four hours of slogging. We’re a little tired and soggy from rain and sweat, but unscathed.

Billy Ridge

The next morning, we wake to find the peaks above us shrouded in fog. So we drink coffee, eat dehydrated oatmeal, and enjoy the break from climbing. When we do get to see the mountain through breaks in the clouds, the scene is awe inspiring. Before us stands a steep, pyramid-like peak that connects to a knife-edge ridge system that wraps in a U shape around us.

Lucas has the very limited guiding rights to this unit, and he got a tip about this specific spot from a salty veteran guide who no longer hunts goats. Lucas has guided more than 60 mountain goat trips, but this is his first hunt on this ridge system.

“It’s like walking on the moon,” he says. “No one has hunted here in more than 30 years.”

This is just one tiny slice of the immense, 17-million-acre Tongass National Forest, the largest remaining temperate rainforest in North America. The forest of old-growth cedar, hemlock, and Sitka spruce represents 12 percent of the nation’s stored carbon in all national forests. It’s home to blacktail deer, five species of salmon, Alexander Archipelago wolves, some 1,700 costal brown bears, and, of course, mountain goats. Two months after my hunt, in October 2020, the Trump administration will remove roadless protections in the Tongass to allow more development and old-growth logging (the move was eventually overturned by the Biden Administration). Most locals, like Lucas and Bjorn, petition hard against more development that would alter the remaining old-growth forests. And I can see why, looking out over this patch of untouched wilderness that has not been hunted in my lifetime. I’ve never been to a place quite like this before—most people haven’t.

I can visualize a careless step, then the sliding loose rocks, a desperate grabbing for handholds that don’t exist, and finally a bone-crunching crash.

Through one of the breaks in the clouds, Lucas spots a mountain goat on the distant ridge—he’s opposite us on the ridgeline. I haven’t seen many mountain goats in my life, but when I pull up my binoculars, I know almost instinctually that he’s a billy. He’s facing toward us, into a chilly, wet wind, seemingly without a care in the world. His powerful shoulders give him the vibe of a bodybuilder. Even though it’s early in the season and he hasn’t yet grown his full snow-white winter coat, he’s nothing short of magnificent.

“How do we get over there?” I ask.

“We don’t, or at least not right now,” Lucas says.

The peaks around us continue to disappear and reappear among the clouds. We can’t get a full view of the ridgeline we’d have to traverse to reach the billy. Even though he’s only some 3,000 yards from us in a straight line, going directly down our side of the ridge and then back up his side is impossible—it’s too steep and nasty. Charging after him in the fog would be foolhardy, Lucas says. After all, a goat could appear on the slope right above us.

But as the day wears on, no goats appear above us. A strong north wind clears the mountains, and we get a full picture of the ridgeline. It looks steep, gnarly, and borderline dangerous. Another billy shows up to join our friend on the far side of the U, and we inspect the ridgeline route even more diligently with our optics.

A plan is developing, but we don’t talk about it, at least not yet. We take a little hike a quarter of the way up the pyramid peak to stretch our legs and get a different angle on the ridge. From there we spot a whole band of goats—24 nannies and kids—grazing and lounging on the slope below. I watch the goats, amazed at how comfortable they are on almost-vertical terrain, while Lucas picks apart the ridge with his binocular.

“I think we can make it,” he says, finally.

“I think we can too,” I reply, even though I really have no idea what I’m talking about.

From this point until the shot, I understand that my job is all about attitude. I’ve been on enough guided hunts to know that a positive, hopeful attitude is often the difference between success and failure. There will be a hard climb for all of us in the morning. If I stay upbeat and engaged, Lucas will keep pushing. If I start to gripe or second-guess, Lucas will start to question too: Does this guy have what it takes? Is he going to keep it together when we’re on the edge? If I do my part, will he do his? I’ve seen the dynamic between guides and hunters break down on duck hunts and in whitetail camps. All it takes is for one member of the group to falter, and the hunt will fall apart. But all of that gets amplified here in the mountains.

“A lot of hunters, regular hunters, aren’t built for this,” Lucas told me earlier in the trip. “I’ve had hunters quit on me. They take everything out of their pack and just walk down.”

I know that John, an experienced Alaskan hunter in his own right, won’t quit. And by the time we make it back down to camp and tuck in for the night, I know that I won’t either.

The Big Climb

The billy is too far away to hike to, relocate, shoot, and pack back to our camp in one day. So our plan is this: We’ll go ultralight (one tent between us and no unnecessary gear or food) and start climbing early in the morning. We’ll ascend the pyramid peak, side-hill our way to the knife-edge ridge, traverse the top of the ridge, descend a wicked-steep shale slope, and then hopscotch our way over a boulder field. From there we’ll climb one more small peak and hopefully spot the billy in the same area we saw him the day before. Even though the goat was a good distance away, he was hanging out in a great place for us—a relatively flat ridgetop. I’ve heard several stories about goats that were shot on steep slopes and then slid into oblivion, never to be recovered. That doesn’t seem to be an issue here.

We execute our plan, carefully and flawlessly. At one point, Lucas turns back to us before creeping across a skinny catwalk: “Hold on to the rock before taking your next step,” he says. “Three points of contact at all times. Be really careful.” Both John and I follow the instructions, looking for our next steps and handholds and not at the 500-foot drop below us.

And for our effort, we’re greeted with the sight of a billy goat—not on a ridge that’s still a day away, but here, in the present. Lucas pokes his head over a ledge and then turns back to us: “There’s a goat bedded down there.”

We drop our packs and crawl up to the edge to look down at the goat below. He’s about 300 yards downhill, lying on his side and facing away. He looks like a golden retriever tired out from a game of fetch—except he’s all white and weighs probably 300 pounds. Through his spotting scope, Lucas confirms that he’s a billy (mostly by evaluating the thickness at the base of his horns).

I get my rifle set up, rest on a backpack, and chamber a round. We debate taking the shot while he’s in his bed but decide against it. The angle is no good. So we wait.

The goat stays in his bed, barely moving, but he disappears and then reappears as fog blows across the ridge. It’s not like he’s completely visible and then fully disappears. It’s more like a mirror fogging and then unfogging, the picture getting worse, almost imperceptibly, until it’s gone. This makes me nervous at first, but then it becomes normal. It feels as if he’ll be there forever, and I enjoy watching him. Lucas wonders aloud how long it will take to pack him out.

A full 30 minutes later, the goat stirs from his bed and stands up. We’re beyond ready for him, but he walks straight away from us and evaporates behind a cloud of fog.

When the cloud rolls through and the billy appears once more, he’s still at about 300 yards, quartering away slightly.

OK, here we go… Boom.

The shot hits him somewhere behind the shoulder, and he bucks like a rodeo bull. “Hit him again,” Lucas says as I’m racking another round. He’s moved only a few steps, quartering away now, and I hit him once more, closer to the shoulder. Now he turns directly away, headed for a dip in the terrain, wobbly, and he stops, facing directly away. I zing a rushed shot past his neck, but it seems the first two bullets did their jobs, and the billy lies on his side.

“Once more, we don’t want him to get out of sight,” Lucas says. The fourth bullet hits him through the spine, between the shoulders, killing him where he lies.

The billy is completely still for a full two seconds, then he gives one final kick and tips over below the dip in terrain…out of sight. He’s gone not 50 yards from his bed.

“Oh no, oh no,” Lucas says.

“Can you see him? How far do you think he went down?” But I already know the answer.

“I have no idea,” Lucas says. “You guys pack up and I’ll go and see where he’s at.”

When we catch up with Lucas, he’s standing on the edge of a 1,000-foot cliff, looking down. That little dip in terrain that the goat rolled over leads to a small, steep rock chute, which drops to a massive cliff of which we cannot see the bottom. We talk, but I’m not sure what about. I would like to sit down and cry, but I don’t want to do it in front of my buddies.

So instead, I follow Lucas as he cautiously edges his way down the chute, hoping to get a look at the bottom. It’s steep enough that we are climbing with our hands and feet. It’s steep enough to make the hair on the back of my neck stand on end. A fall here is almost certain death. He finds some white hair, but we never can get a view of the bottom. John waits for us, wisely, at the top of the ledge. The goat is gone.

Tragedy, Real and Imaginary

That night we camp at the top of the ridge. In the morning we try several different routes down, still hoping to find the goat, but all those routes eventually cliff out. So we hike all the way back out to our original camp and then down through the timber to the beach. The next morning, one of Lucas’ buddies comes with a jet boat, and we attempt to boat up the river valley and approach the cliff from below. But just a mile in, we bottom out the boat and have to turn around. And with that, it is all over.

During the boat ride back to Juneau, on the plane ride home, and for many months after, I felt deplorable about the whole damned thing. I felt bad for myself—I had spent a year hiking, backpacking, and shooting to prepare, and then I’d hunted my hardest, done everything I could, and still failed. I felt bad for Lucas and John, who also gave it their all, on my behalf, only for me to fail. And most of all I felt bad for that great old billy goat, which died quickly but ultimately for no good reason at all.

I talked to a handful of experienced goat hunters, who sympathized with my story. All told me that “it sucks, but it’s part of mountain goat hunting.” That made me feel a little better, but I still found myself replaying the shot sequence over and over in my head each night before falling asleep.

Eventually I googled “Nietzsche” and learned that Friedrich Nietzsche was a famous German philosopher and nihilist who was an invalid for most of his life and eventually went insane. I also found this quote from him, which internet philosophers love to share: “He who climbs upon the highest mountains laughs at all tragedies, real or imaginary.”

Someday, hopefully soon, I’ll get back to Southeast Alaska to hunt with Bjorn again, and when I do, I think I’ll tell him that Nietzsche was full of shit. The mountains might be the best place to experience tragedy, real and imaginary, but nobody laughs.

This story originally appeared in the Alaska Issue of Outdoor Life. To read the whole issue, you can find it on Apple News+ or one of our apps. Read our guide on how existing subscribers can access their digital issues. Or find more OL+ stories.